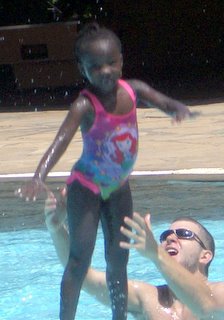

This past weekend the young adult volunteers took a vacation. We went to Mombasa, the large and somewhat historic Kenyan coastal city. After spending the morning walking around town with our unoffical guide Mohammed, we spent the afternoon at the Wema Center where Fiona works. The rest of the weekend was spent lounging on the beach, reading in our wooden beach chairs, playing with little ones in the pool (i.e. throwing them high into the air and not letting them drown- not an easy task, yet extremely fun).

This past weekend the young adult volunteers took a vacation. We went to Mombasa, the large and somewhat historic Kenyan coastal city. After spending the morning walking around town with our unoffical guide Mohammed, we spent the afternoon at the Wema Center where Fiona works. The rest of the weekend was spent lounging on the beach, reading in our wooden beach chairs, playing with little ones in the pool (i.e. throwing them high into the air and not letting them drown- not an easy task, yet extremely fun).

A friend, Leora, and I went to Sheldrick Elephant Orphange, one of three like it in the world. From 11am-12pm each day, visitors can come and see these orphaned animals being trained to return to the wild. Poaching is still a very real problem in this area, with tusks cashing in around $1,000 per elephant. The Kenyan Wildlife Service has done a remarkable job and elephant populations have been on the rise since the late 70's. However, cuts in funding have decreased their capability to respond to the program. Through private initiatives like Sheldrick, baby elephants are nurtured and returned to the wild.

A friend, Leora, and I went to Sheldrick Elephant Orphange, one of three like it in the world. From 11am-12pm each day, visitors can come and see these orphaned animals being trained to return to the wild. Poaching is still a very real problem in this area, with tusks cashing in around $1,000 per elephant. The Kenyan Wildlife Service has done a remarkable job and elephant populations have been on the rise since the late 70's. However, cuts in funding have decreased their capability to respond to the program. Through private initiatives like Sheldrick, baby elephants are nurtured and returned to the wild. We learned a lot of fascinating information about elephants. Elephants are a lot like humans. They need a lot of attention, and there is always a keeper with one of the elephants, 24/7/365. Yes, each one sleeps with an elephant every night. They travel an average of 30 miles a day, drink up to 50 gallons of water and eat hundreds of pounds daily. Not being able to sweat, they use their thin, fragile ears to fan their bodies and cool off. They also suck out water from their stomachs with their trunks, using the water to spray their bodies and cool off. An elephant crosses its legs while standing in order to rest. They cannot jump but are known to be adept swimmers.

We learned a lot of fascinating information about elephants. Elephants are a lot like humans. They need a lot of attention, and there is always a keeper with one of the elephants, 24/7/365. Yes, each one sleeps with an elephant every night. They travel an average of 30 miles a day, drink up to 50 gallons of water and eat hundreds of pounds daily. Not being able to sweat, they use their thin, fragile ears to fan their bodies and cool off. They also suck out water from their stomachs with their trunks, using the water to spray their bodies and cool off. An elephant crosses its legs while standing in order to rest. They cannot jump but are known to be adept swimmers.

The dams must be managed properly, however, or else they will erode away. Cattle must not walk on the dam itself. A fence is built around some of the dams to prevent contamination by animals, but this restricted access frustrates herders. Also, the waters from each rain wash silt into the dam, necessitating desilting with heavy machinery every 5-7 years. If there is an effective water managing committee, they can charge user fees and spend this money to maintain and improve the dam structure.

TD Jakes came to this area in September, supplying money for a water tank, borehole, troughs, pump and generator. Oftentimes, animals bathing in the dam water make it unsuitable for human drinking. With a borehole and generator to pump water from aquifers below, the Maasai now have ready access to safe water. They will collect user fees for humans and animals, using this money to pay for diesel to run the generator and for needed maintenance repairs .

CWS also encourages communities like this one to use this project as an asset for investing in their own future. For instance, the group has expressed its desire to pipe water to nearby schools. Instead of asking CWS for more money, they will use the excess water pumped from the ground to grow and sell vegetables. In this way, we hope to partner with the community, empowering them to help themselves and others.

This weekend I watched two friends battle it out on the field hockey field. "Field" is a loose term in Kenya, this time meaning a level, hard-packed dirt square with chalked lines. My friends' team, the Eaglets, won their semi-final game 3-1. (Right: Cathy jukes past someone, a-gain.) In the finals they lost a heart-breaker in overtime 2-1 when a girl on the opposing side kicked the ball in (it's illegal to touch the ball with anything but your stick). I think the referees were tired and just wanted the game to end. I've never been one to watch field hockey, but I enjoyed watching my friends play and even got riled up with the poor officiating. But maybe that's just me when I watch sports. I also brought my frisbee along and made a few friends teaching them how to throw. I'm beginning to feel more 'at home' here in Kenya, as I make friends and get involved in daily Kenyan life.

This weekend I watched two friends battle it out on the field hockey field. "Field" is a loose term in Kenya, this time meaning a level, hard-packed dirt square with chalked lines. My friends' team, the Eaglets, won their semi-final game 3-1. (Right: Cathy jukes past someone, a-gain.) In the finals they lost a heart-breaker in overtime 2-1 when a girl on the opposing side kicked the ball in (it's illegal to touch the ball with anything but your stick). I think the referees were tired and just wanted the game to end. I've never been one to watch field hockey, but I enjoyed watching my friends play and even got riled up with the poor officiating. But maybe that's just me when I watch sports. I also brought my frisbee along and made a few friends teaching them how to throw. I'm beginning to feel more 'at home' here in Kenya, as I make friends and get involved in daily Kenyan life.

I arrived today at a school on the outskirts of Nairobi. The school, Mutuini, is part of our School Safe Zones (SSZ) initiative. The idea is to make schools safer for children, in hopes parents will feel confident leaving their children there for the day. So far we have provided money for a new gate and fence around the school, as well as some toilet and water catchment repairs. Our hope is that these improvements would not only improve the school's facilities, but also inspire students, teachers and parents alike to further support the school in whatever way they can.Accompanied by some local leaders, we had a meeting with the parents in the school.

I arrived today at a school on the outskirts of Nairobi. The school, Mutuini, is part of our School Safe Zones (SSZ) initiative. The idea is to make schools safer for children, in hopes parents will feel confident leaving their children there for the day. So far we have provided money for a new gate and fence around the school, as well as some toilet and water catchment repairs. Our hope is that these improvements would not only improve the school's facilities, but also inspire students, teachers and parents alike to further support the school in whatever way they can.Accompanied by some local leaders, we had a meeting with the parents in the school.  About 90% of those present were women, many carrying children. I was told that many - if not most - of the homes in this area were female, single-headed househoulds. There are many reasons for this, and traditionally the African man works outside of the house, going into the city, while the woman stays at home to do important housework. These women had walked many miles to arrive for this meeting; to sit in the hot sun, listen to various people talk, and have some white guy take their picture.

About 90% of those present were women, many carrying children. I was told that many - if not most - of the homes in this area were female, single-headed househoulds. There are many reasons for this, and traditionally the African man works outside of the house, going into the city, while the woman stays at home to do important housework. These women had walked many miles to arrive for this meeting; to sit in the hot sun, listen to various people talk, and have some white guy take their picture. Many people gave speeches, and many more listened. My coworker Sarah thanked the parents for coming, saying how they were an integral part to the initiative. A representative from the government stressed the importance of education in poverty reduction. Two counselours spoke about alcoholism, one treating it as a disease and the other as lack of affection in the home. I had known that alcoholism was a problem, but was surprised at how matter-of-factly the community admitted women were routinely beaten by their husbands.

Many people gave speeches, and many more listened. My coworker Sarah thanked the parents for coming, saying how they were an integral part to the initiative. A representative from the government stressed the importance of education in poverty reduction. Two counselours spoke about alcoholism, one treating it as a disease and the other as lack of affection in the home. I had known that alcoholism was a problem, but was surprised at how matter-of-factly the community admitted women were routinely beaten by their husbands.